Dreaming Is the New Thinking

The next leap in intelligence won’t purely come from bigger models, it’ll come from machines that can imagine their own futures.

When DeepMind’s AlphaGo defeated Lee Sedol in 2016, it didn’t just win by reacting to board positions, it won by thinking ahead and simulating futures that hadn’t happened yet. While AlphaGo used explicit tree search, most agents have operated more like reactors than reasoners, mapping observations directly to actions without ever building an internal intuition of how the world works. But what if agents could do more than respond? What if they could imagine, predict, and plan through simulations before even taking a single step?

Introduction

For decades now, RL has achieved remarkable success without explicitly understanding the dynamics of the environments it operates in, agents learn through pure trial and error. Intuitively this feels incomplete, after all humans don’t navigate the world through blind response patterns; we build mental models that let us imagine consequences before we act. The same principle must apply to agents as well; they perform better when they understand how the world evolves and can anticipate what the consequences of an action they take is.

World models give agents exactly this capability, internal representations of environment dynamics that allow them to imagine possible futures hence allowing them to plan and make decisions that are more sample-efficient and robust than pure reactive policies.

History

The deep learning revolution in reinforcement learning began with model-free breakthroughs (DQN, PPO etc.) enabling robust policy optimization across diverse tasks. These algorithms bypassed the need to ever learn model environment dynamics. Their impressive sample efficiency improvements and generalizability across complex domains shifted the field’s attention away from world models for nearly a decade.

When you can train an agent to achieve superhuman performance without explicitly predicting how the world works, why bother with the added complexity of learning dynamics models that might be inaccurate or computationally expensive?

Early World Models

Ha and Schmidhuber’s world models (2018)

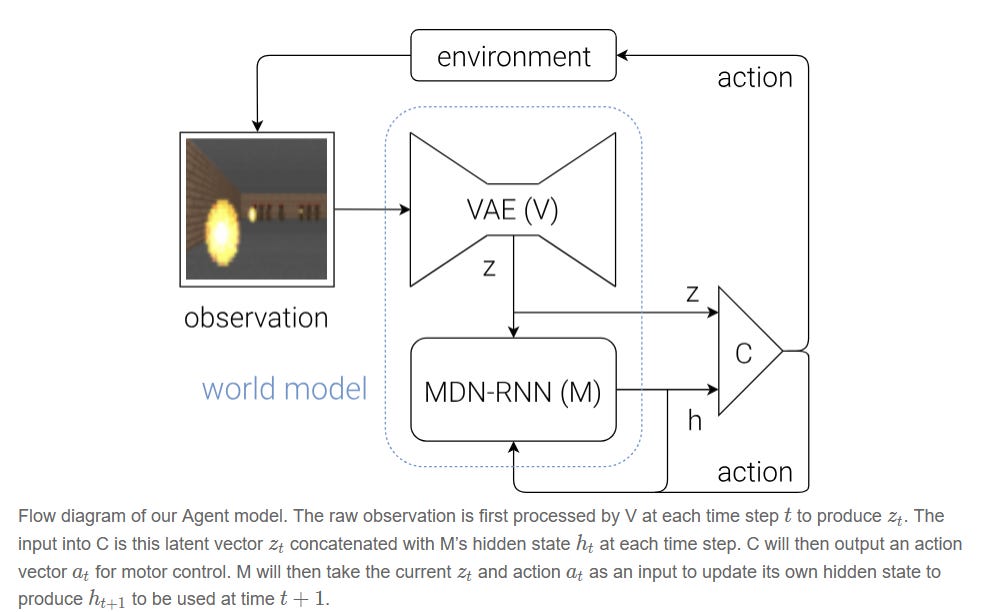

Ha and Schmidhuber’s paper on world models rekindled interest in learning internal simulators of the world by showing that agents can literally learn to dream and those dreams could be good enough to train in. The paper’s architecture splits the agent into three parts - a VAE compresses raw pixels into a latent representation, an MDN-RNN learns to predict what comes next as a probability distribution over future states, and a tiny linear controller decides what actions to take based on the compressed present and predicted future. What made this work popular wasn’t just the technical success (solving CarRacing-v0 and exceeding VizDoom leaderboards) but it was the idea that you could train an agent entirely inside its own imagined environment, then deploy it to reality and watch it perform well. This breakthrough shifted the field’s conversation from “can we learn world models?” to “how far can we scale them?”, inspiring a wave of research on world models.

PlaNet (2019)

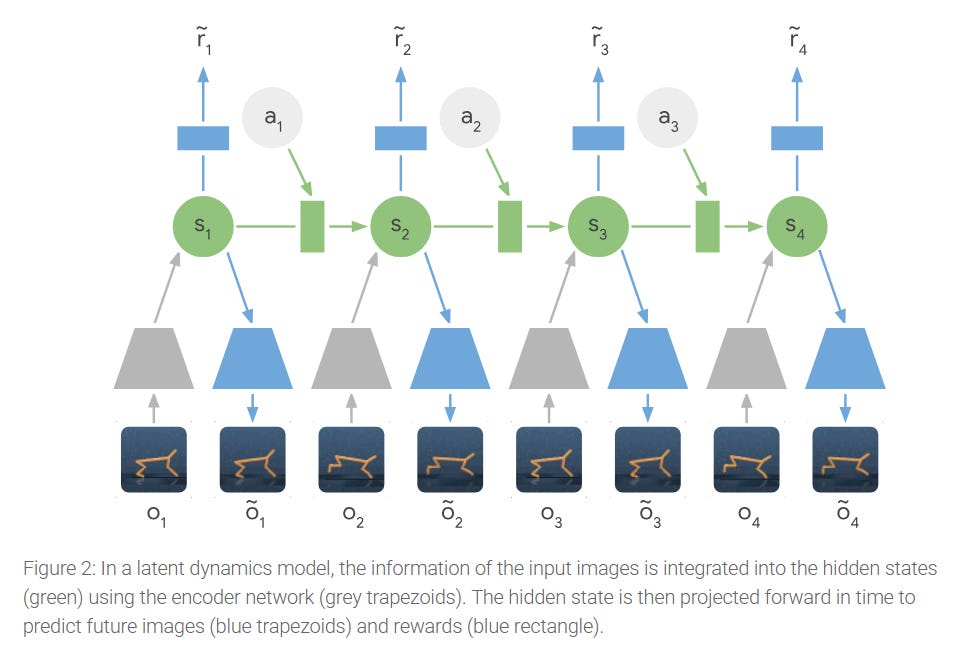

The PlaNet represented an advancement in world models that changed how we think about learning and planning in imagination. While the seminal 2018 World Models paper demonstrated that agents could learn compact representations of environments and use them for control, it relied on training a separate controller and was limited to relatively simple tasks. PlaNet on the other hand introduced a latent dynamics model that combines both deterministic and stochastic components, the Recurrent State-Space Model that enabled the model to remember information reliably over time and capture uncertainties over multiple possible futures. This coupled with direct planning via Cross Entropy Method in the learned latent space rather than using a separate policy network, allowed PlaNet to solve substantially more complex continuous control tasks from raw observations.

Modern World Models

Dreamerv3 (2023)

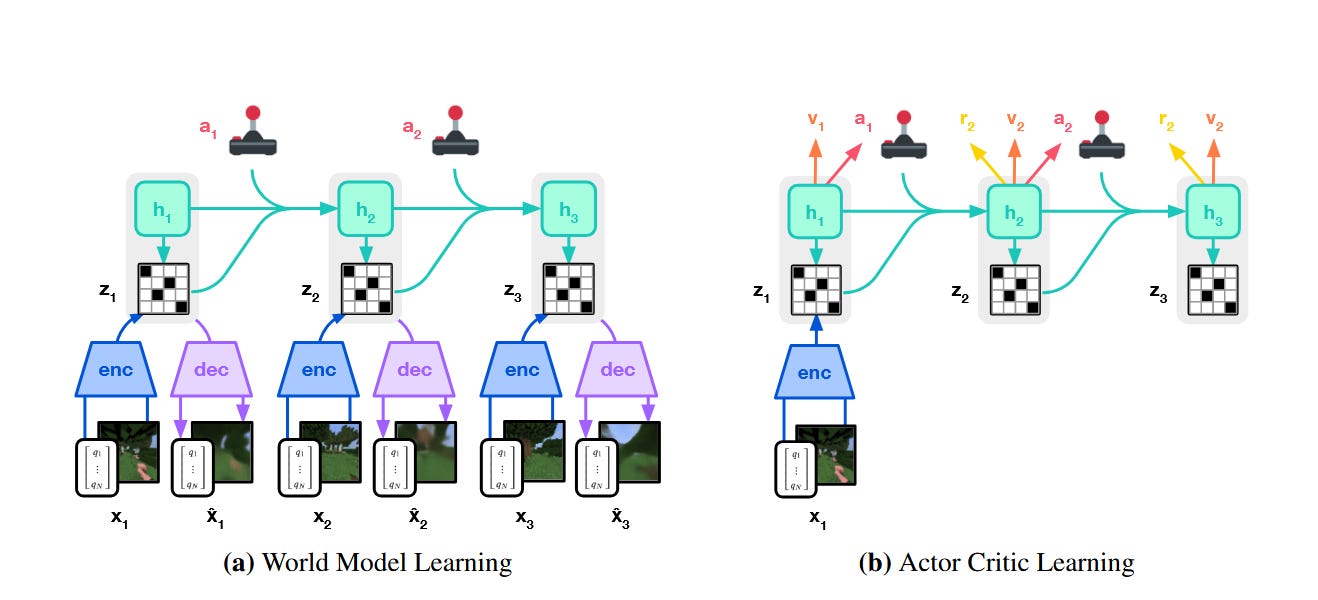

DreamerV3 was an important moment in reinforcement learning by finally delivering on the promise of a general-purpose learning algorithm that works across diverse domains without domain-specific tuning. DreamerV3 evolved through two prior generations (DreamerV1 and V2) to address the fundamental problem that plagued model-based RL: the tendency for learned world models to either explode with large prediction errors or collapse into uninformative representations when facing the vastly different reward scales, observation complexities, and temporal dynamics in different environments (Atari, continuous control, open world environments etc.). Their breakthroughs were robustness techniques that ensure the world model does not collapse into the same errors plaguing previous world models. Some of the ideas they explored were symlog transformations that compress both large and small values symmetrically around zero, a “symexp twohot” loss that represents predictions as categorical distributions over exponentially-spaced bin, percentile-based return normalization that adapts exploration to reward sparsity, and a carefully balanced KL objective with “free bits” that prevents the world model from either ignoring visual details or overfitting to noise.

Most remarkably DreamerV3 became the first algorithm to collect diamonds in Minecraft from scratch, a challenge requiring 20+ minutes of farsighted planning with sparse rewards in procedurally generated worlds while simultaneously achieving SOTA results on over 150 tasks spanning 8 benchmarks with a single set of hyperparameters.

This work shifted the paradigm from viewing world models as brittle components to treating them as robust foundation models for decision-making, opening pathways toward agents that can learn general world knowledge from diverse data and transfer it across tasks.

IRIS (2022)

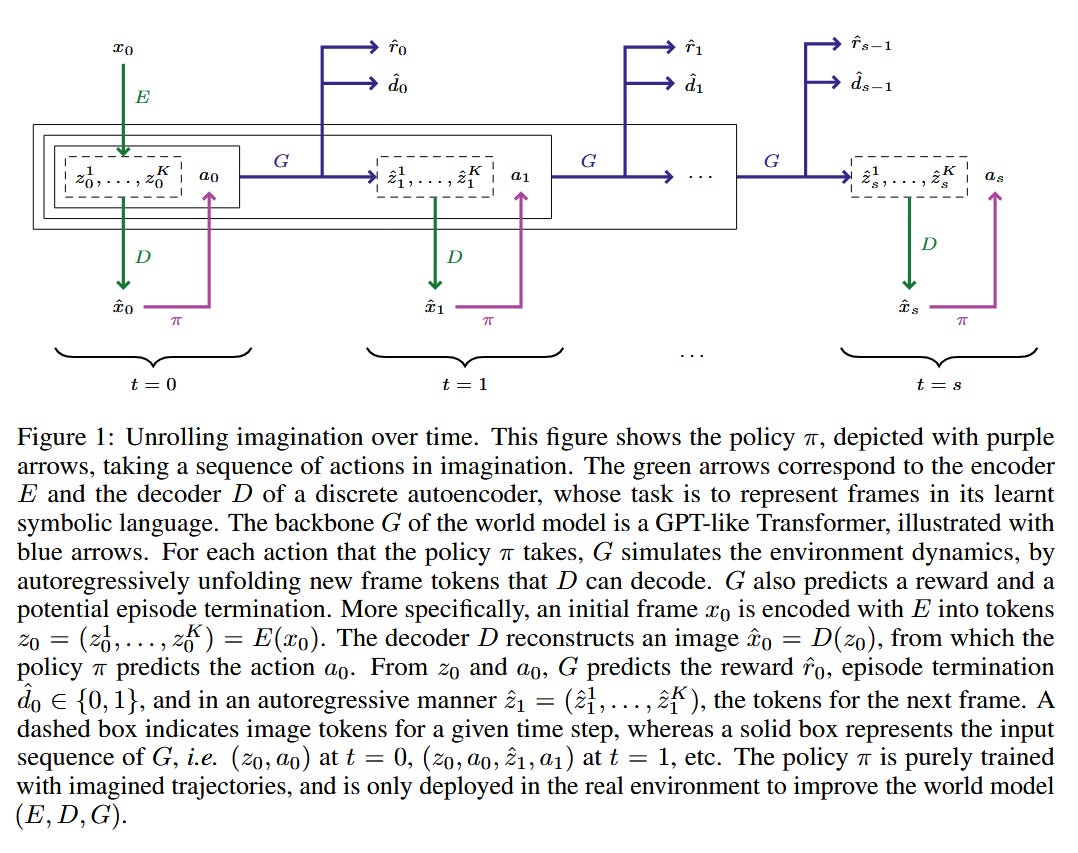

The IRIS paper demonstrated that Transformers can serve as highly sample-efficient world models for complex visual environments. Building on top of previous work IRIS introduced a novel architecture that replaces traditional recurrent networks with a discrete autoencoder paired with an autoregressive Transformer. The key innovation was in casting environment dynamics as a sequence modeling problem, frames are tokenized into discrete symbols, and a Transformer autoregressively predicts future tokens, rewards, and episode terminations based on actions taken. What made this particularly impactful for the field is that it validated Transformers as viable alternatives to recurrent architectures for world modeling, opening new pathways for more massively parallel architectures.

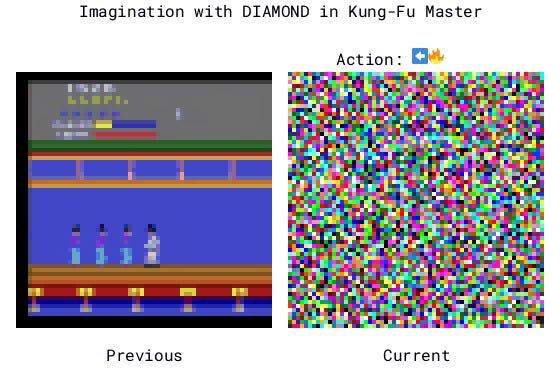

DIAMOND (2024)

DIAMOND (DIffusion As a Model Of eNvironment Dreams) introduced the first successful application of diffusion models to world modelling for RL and achieved SOTA performance then in the Atari 100k benchmark. The key innovation they did was to adapt an EDM (Elucidating the Design Space of Diffusion Models) diffusion framework instead of traditional DDPM to generate stable, high-fidelity video predictions directly in pixel space with just 3 denoising steps which challenged the prevailing idea of direct latent state representations that were used by IRIS and Dreamerv3. Beyond benchmarks, the authors scaled their approach to model complex 3D environments like CS:GO , creating an interactive neural game engine that laid the framework for future work for world models to generate interactive environments.

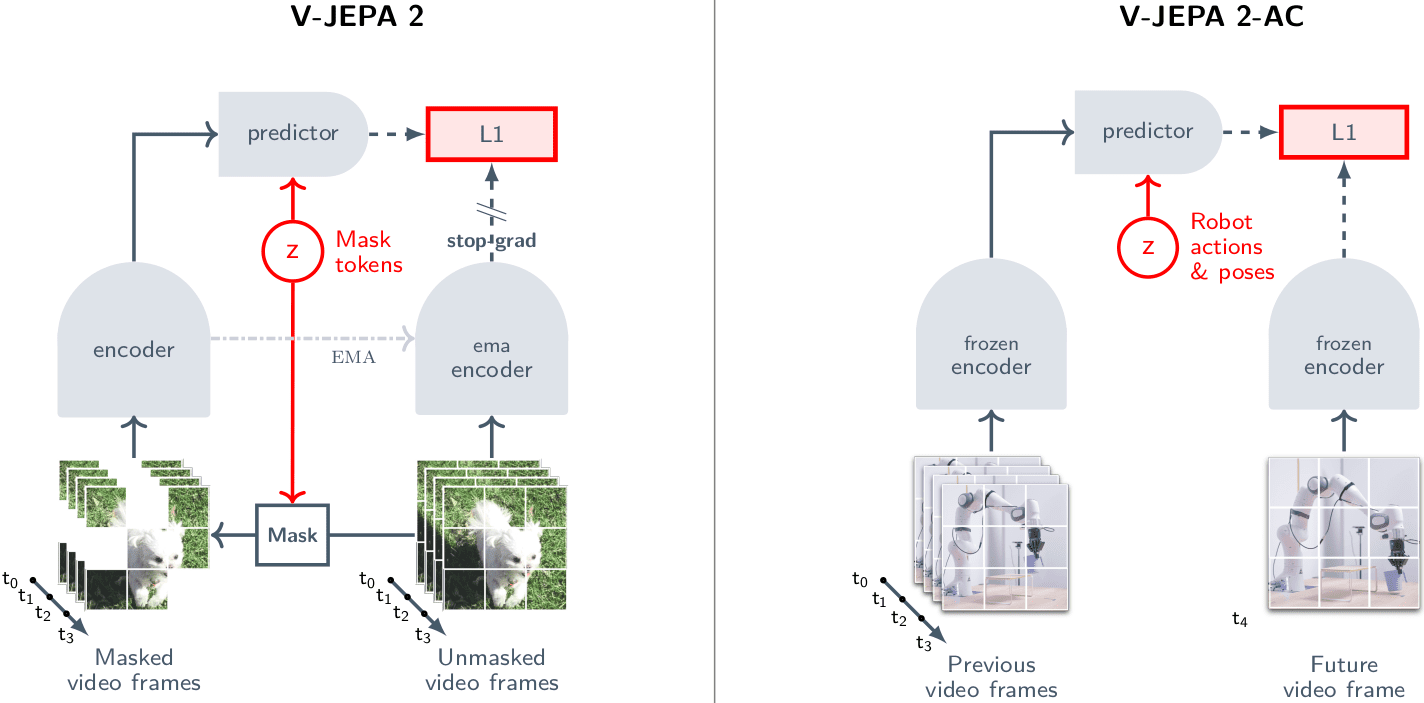

V-JEPA 2 (2025)

V-JEPA 2 is one of the more recent breakthroughs in world models and showed a clear shift towards a new type of world model . One of the most impressive aspects of V-JEPA 2 is its ability to learn a robust world model primarily through self-supervised observation from vast amounts of internet video data, complemented by a relatively small amount of robot interaction data. This is a game-changer because it moves away from the prohibitive need for extensive, hand-labeled interaction data, which has long been a bottleneck for scaling up robot learning. One of the most insane achievements that V-JEPA 2 achieves is how it integrates with LLMs. By aligning V-JEPA 2 with an LLM, the system demonstrated state-of-the-art performance on multiple video question-answering tasks, including an impressive 84.0% on Perception Test and 76.9% on TempCompass. This is particularly notable because it shows that a video encoder pre-trained without any language supervision can still be effectively aligned with an LLM to achieve top-tier performance on complex video-language tasks, challenging conventional wisdom in the field.

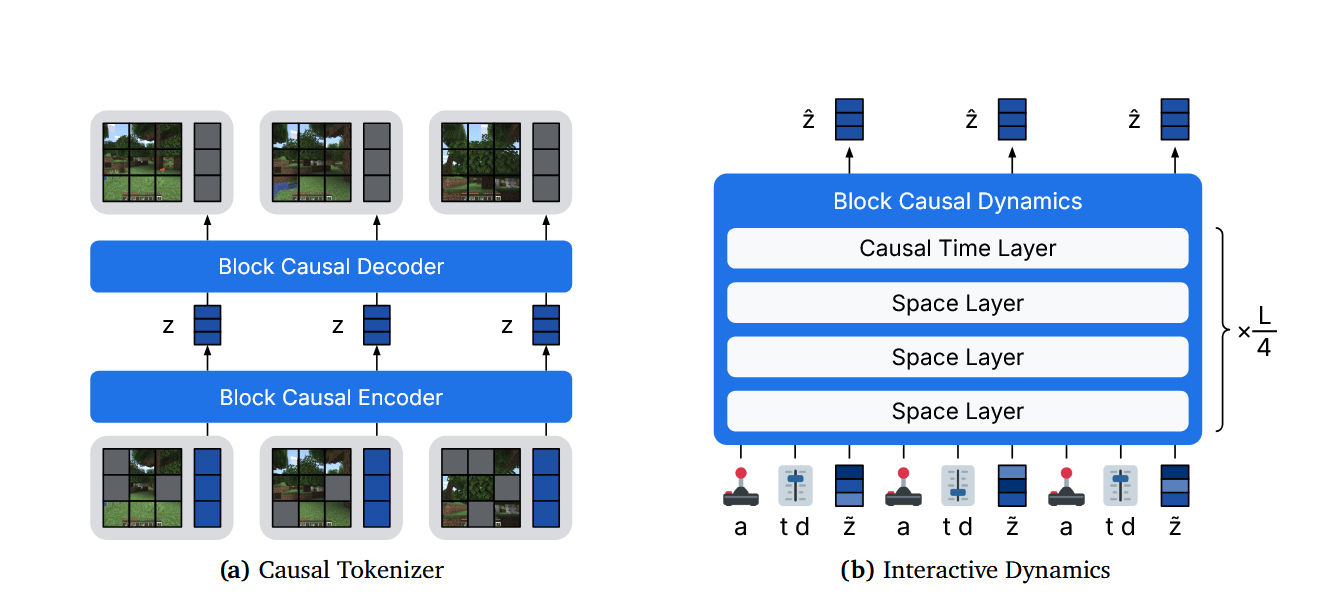

Dreamer v4 (2025)

Unlike earlier world model agents that depended heavily on interacting with their environments (e.g., Atari or small simulation benchmarks), Dreamer V4 represents a major leap by learning purely from videos and demonstrated its power by being the first agent to obtain diamonds in Minecraft without ever playing during training. The key innovations are in efficiency and scalability: “shortcut forcing” allows its diffusion model to generate video in just four steps instead of the usual 64, making real-time learning feasible, while X-prediction stabilizes long rollouts by directly predicting clean frames. Interestingly, Dreamer V4 shows strong generalization, achieving near full performance with only a fraction of labeled action data and transferring learned behavior across unseen environments. This shifts world models from tightly coupled, interaction-bound systems to flexible, scalable learners that can absorb vast, unlabeled real-world video data.

The Benchmarking Problem (what’s broken with how we judge world models)

Benchmarks shaped the field of RL, but they are also used to mislead. Current popular benchmarks (Atari, narrow robotics tasks, curated simulators) distort incentives and hide the real challenges of building world models that matter in real life.

The key problems that current benchmarks pose are -

Real-world transfer gap. High scores on simulated tasks rarely predict performance in noisy, partially observed, physically grounded environments. Models tuned to simulator idiosyncrasies break when exposed to real sensors, unexpected physics, or distributional shift.

Lack of causal understanding and interpretability. Many world models compress the world into latent dynamics that are effective to “solve” benchmarks but opaque to humans. Without interpretable causal structures it is hard to know when a model will generalize or to debug catastrophic failures.

Long horizon planning difficulty. Benchmarks that reward short episodes or dense reward signals encourage myopic strategies. Real tasks often require long term planning under uncertainty and incremental score gains on short tasks don’t measure that.

Gaming the benchmarks. Researchers often overfit to evaluation suits and choose seeds that score high rather than improving core generalization or reasoning capabilities.

Atari-100k as a benchmark

It’s easy to dismiss “ALE/Atari” as a solved benchmark after all many RL agents now play Atari games at or above human level. But as argued in In Defense of Atari by Pablo Samuel Castro, that view completely misses the point of what Atari was meant to be: not an end goal, but a research platform. Over the years, Atari has become the perfect place to introduce a fancy idea, test it on Atari, show a few points of aggregate improvement over a baseline, claim SOTA. But under those plots, the story is far more nuanced: small leaderboard gains often mask massive sensitivity to hyperparameters, inconsistent per-game performance, and brittle generalization.

This hyperparameter sensitivity elicits a harder question: if we can’t make agents work reliably on Atari, how can we hope to scale them to messy, real-world systems? That’s exactly why Atari still matters. Its diversity of environments, deterministic and stochastic variants, and now continuous action extensions make it a uniquely rich testing ground. Unlike many modern benchmarks, Atari games weren’t designed for RL, they were designed for humans which helps reduce experimenter bias.

The real lesson is not to stop using it, but to use it properly. Stop treating IQM scores as proof of progress. Report per-game behavior, sensitivity analyses, robustness across data regimes. Use Atari to ask why the algorithm works, not just whether it gets a better score. Chasing the leaderboard is easy but building methods that are robust, transferable, and interpretable on a platform as well-understood as Atari is hard and far more meaningful for the future of world models.

Future directions

If world models are to move from lab experiments to practical engines of planning and control, research should focus on several concrete directions.

Design better benchmarks. Create benchmark suites that explicitly test transfer, long horizons, partial observability, and real noise. Include cross-domain suites and stress tests.

Bridging sim-to-real at scale. Exploit large unlabeled video datasets for diverse and open world dynamics while using small, high-quality labeled interaction datasets to anchor domain specific understanding. Methods that show strong few-shot adaptation from simulated or internet video to real robots will be crucial.

Interpretable world models. Develop inductive biases and architectures that yield disentangled causally meaningful latent representations. Tools for inspecting and intervening in learned dynamics are needed.

Algorithmic efficiency and interactive generation. Progress like shortcut forcing or reduced-step diffusion matter because practical agents must imagine and plan in real time. Invest in model architectures and generative methods that trade off fidelity for speed in controllable ways.

Community practices and reproducibility. Standardize reporting, hyperparameters, compute budgets, ablations, and seeds. Share datasets, pretrained world models, and evaluation harnesses to make comparisons meaningful.

Open questions in world models

What is the right abstraction? Are current latent spaces (dense vectors, transformers over tokens) the best medium for causal, long-horizon reasoning or do we need symbolic/hybrid representations?

How to reliably extract actions from passive video? We can learn representations from videos but how do we map those to policies robustly when action labels are scarce?

How to evaluate causality and build causal systems? Can we design universal probes that measure whether a model understands interventions and counterfactuals, beyond correlational prediction?

How do we plan over extremely long time horizons efficiently? Real world problems like robotics require reasoning over minutes or hours. How can models avoid compounding errors and remain coherent over thousands of steps?

What principles underlie generalization in world models? We still don’t have a solid theory explaining why some architectures generalize across tasks and others don’t.

Are world models necessary or just convenient? There’s an ongoing debate between model-based and model-free RL. Are explicit world models essential for intelligence or just one path?

Conclusion

The domain of RL is constantly shifting. For years research has orbited around narrow benchmarks like Atari where incremental gains on leaderboards was seen as meaningful progress. But systems like Dreamer v4 represent a turning point, training powerful models from raw videos and scaling to open-ended environments like Minecraft, and demonstrating the ability to generalize.

Technical breakthroughs alone aren’t enough though, benchmarks should be stepping stones, not destinations. The real frontier lies in agents that can imagine, plan, and act robustly in open-ended worlds, not just optimize a score in a fixed game. That means rethinking how we evaluate progress: measuring causal understanding, transferability, long-horizon reasoning, and robustness.

World models are still in their infancy and fundamental questions around abstraction, causality, interpretability, robustness, and scaling remain unsolved. But the direction is clear, the next leap will come from building systems that understand and navigate the world in a way that generalizes.

The end game is not just higher scores on benchmarks but agents that can imagine, predict and act in messy open world environments. That is the real measure of intelligence we are racing towards.

References:

1. World Models (Ha & Schmidhuber, 2018)

2. Learning Latent Dynamics for Planning from Pixels (Hafner et al., 2019)

3. Mastering Diverse Domains through World Models (Hafner et al., 2023)

4. Transformers are Sample‑Efficient World Models (Micheli et al., 2022)

5. Diffusion for World Modeling: Visual Details Matter in Atari (Alonso et al., 2024)

6. Training Agents Inside of Scalable World Models (Hafner et al., 2025)

7. In Defense of Atari - the ALE is not ‘solved’!

The author, Akshat Singh Jaswal is a research intern at Lossfunk.

Very interesting article and well-researched. My master's thesis was on Auto-encoders and anomaly detection algorithms. I am definitely optimistic that machines will imagine better with time, giving more profound intelligence in the future.

Regarding the topic of the article, brilliant on world models! My brain simulates coffe breaks.