AI is the future of Market Efficiency

The coming era of Intelligence Arbitrages

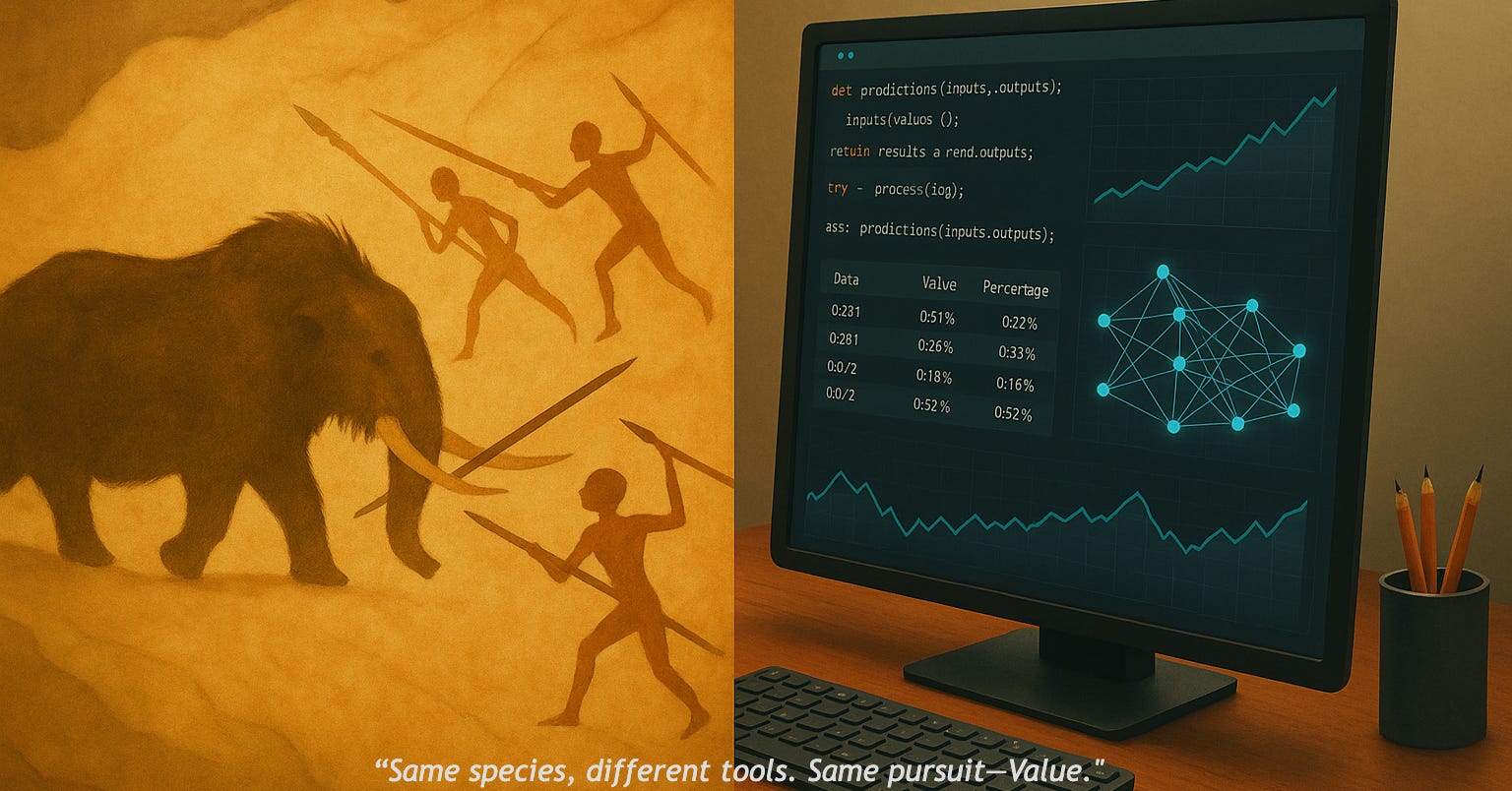

We are creatures of value

A few thousand years ago, humans were crafting tools to bring down mammoths. Fast forward to today, and we are now crafting mathematics and technology to replicate our own intelligence. Yet, every other mammal has remained virtually unchanged. The singular quality that defines us is our infinitely creative and malleable nature — capable of profound transformation in our quest for value. Much like a neural network, a universal function approximator that can model any function, we are universal value approximators— capable of recognizing and creating any form of value.

Collective Intelligence

In 1906, statistician Francis Galton conducted an interesting experiment in which he asked a crowd to guess the weight of a cow. He found that the median guess was 1,207 lbs, while the actual weight was remarkably close at 1,198 lbs. He referred to this phenomenon as the wisdom of the crowd. A modern example of this can be seen in the 2024 U.S. elections, where Polymarket—a prediction market—accurately forecasted the results hours before they were officially announced, outperforming expert polls and pundits.

This concept of collective intelligence, where higher-level intelligence emerges from the collaboration of many, is pervasive across systems like open-source software, democracy, Wikipedia, and even financial markets.

“As a collective, we are remarkably effective at predicting value.”

But why do collectives work so well?

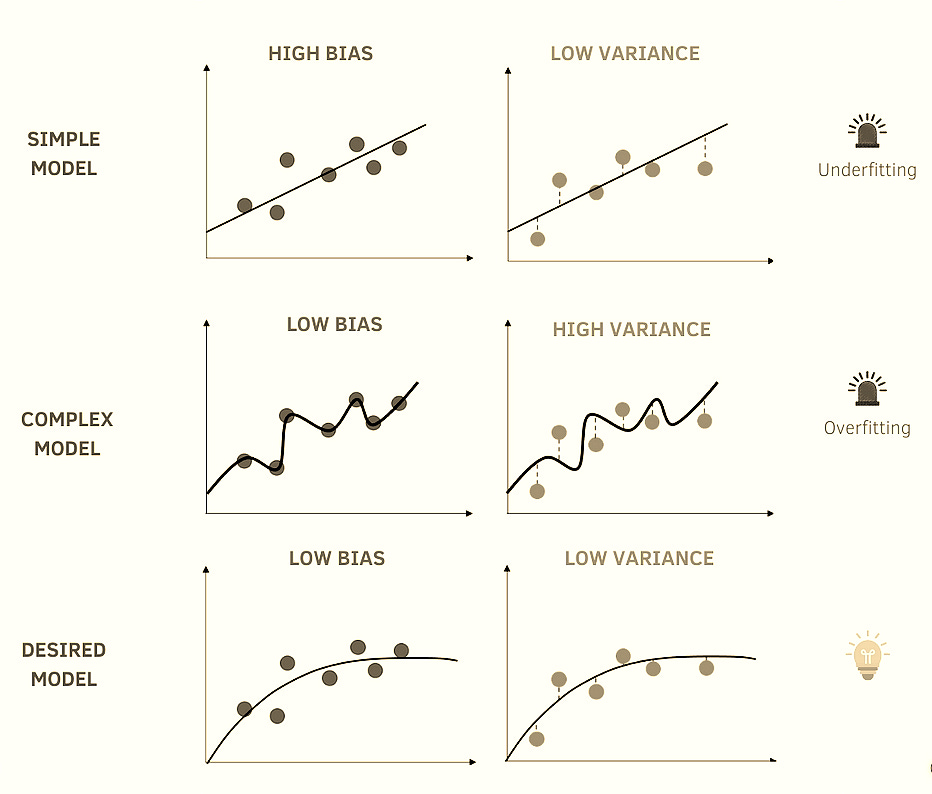

Model ensembling is a powerful technique commonly used in machine learning. You get a free accuracy boost simply by taking a majority vote from several models that are identical in every way—except for their initial random weights. Broadly, there are two reasons for errors in ML: Bias and Variance. Bias occurs when the model is not sophisticated enough to capture the underlying patterns in the data (underfitting), whereas variance occurs when the model has memorized the training data and does not generalize well to new data (overfitting).

When you combine multiple models, strong predictions made by individual models are reinforced (reducing bias), while weak or noisy predictions are averaged out (reducing variance). This is precisely how collective intelligence works: individuals, each with their strengths and weaknesses, come together as an ensemble, resulting in more accurate predictions—and thus, minimizing error in the process.

“Markets, at their core, are just ensembles.”

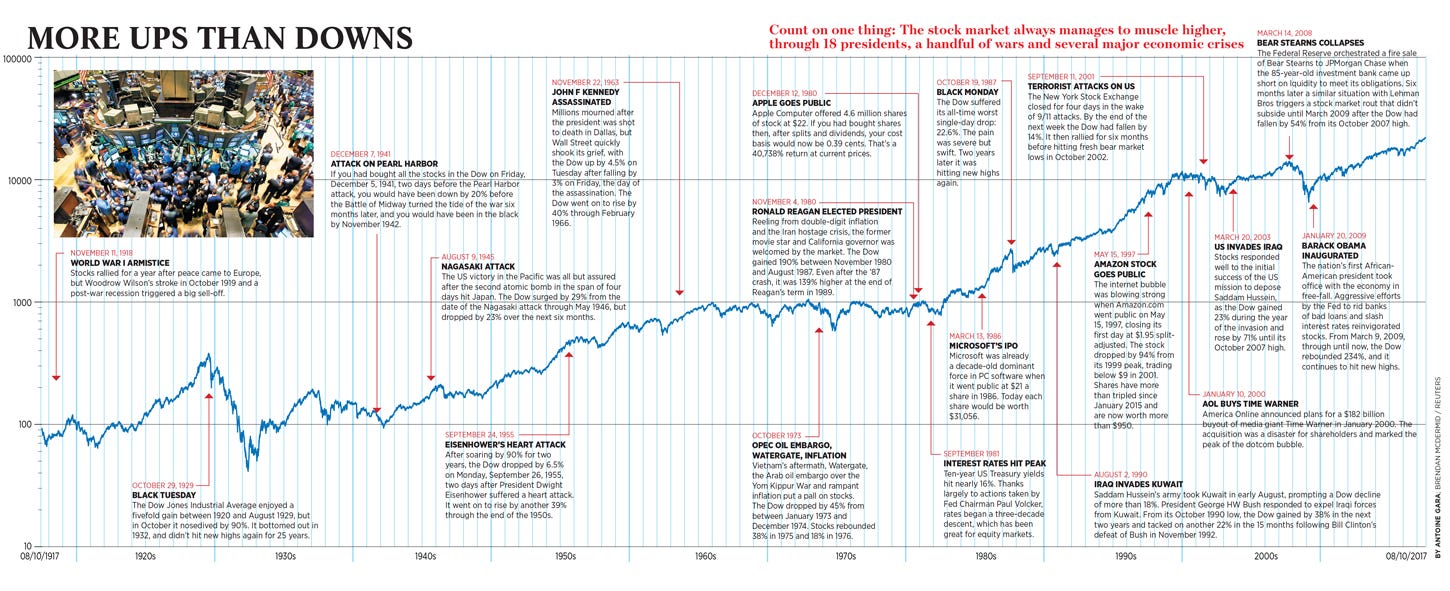

Markets are the heartbeat of civilization

Look back over the last 100 years of the stock market, and you’ll find that every major historical event—from wars and pandemics to recessions and assassinations—has been captured in its movements. A millennia from now, the markets will give a snapshot of our history to humans of the future.

It’s as if every minor and major event in our world is being continuously processed and priced in by the market. This idea is referred to as the Efficient Market Hypothesis - asset prices at all times reflect all available private and public information.

A scorching summer? Priced in.

A tweet from Trump? Priced in.

A handful of sick people in a wet market in China? Priced in.

Every butterfly flutter is resonated by this one number.

Markets are a distributed compute cluster

Markets can be viewed as a massive distributed compute cluster—powered by intelligent individuals, each with their own unique value systems, experiences and information. Cumulatively, they process the world's data to make continuous and accurate predictions about the value of assets. This collective value estimation is also why capitalism thrives as opposed to centralized planning where pricing decisions are made by a single committee. When everyone participates in price discovery, the estimates are more accurate and time and resources can be allocated more efficiently.

So if the market is efficient and everything is already priced in, can it even be predicted?

Here’s the key insight : markets are error-correcting systems that tend toward the truth. What we see is the market’s best estimate of truth at a given point of time. Its function is to self-correct once an error is detected. The real question isn’t whether markets are always efficient, but when they are—and when they’re not. Inefficiencies do exist, and if you can identify them before the market corrects, you can take a counter-position and profit.

“The ones who make the markets efficient are the ones who make money.”

So how does one spot these errors?

It’s important to understand that the current market price is just a sample estimate—it reflects the views of only the participants active at this moment. But the true price lives in the minds of the entire market, including those not currently participating but who might step in if it gets interesting.

To predict inefficiencies, you need to identify the gap between the sample and the population—the difference between the current price and the price the entire market would agree upon if fully engaged. That’s where the opportunity lies.

Patterns of Error

Technical Analysis is traditionally defined as the quantitative study of price and its movements. But I see it differently—it's the study of Patterns of Error. These patterns—repeated formations in price and technical indicators—can signal that the market is currently mispricing an asset.

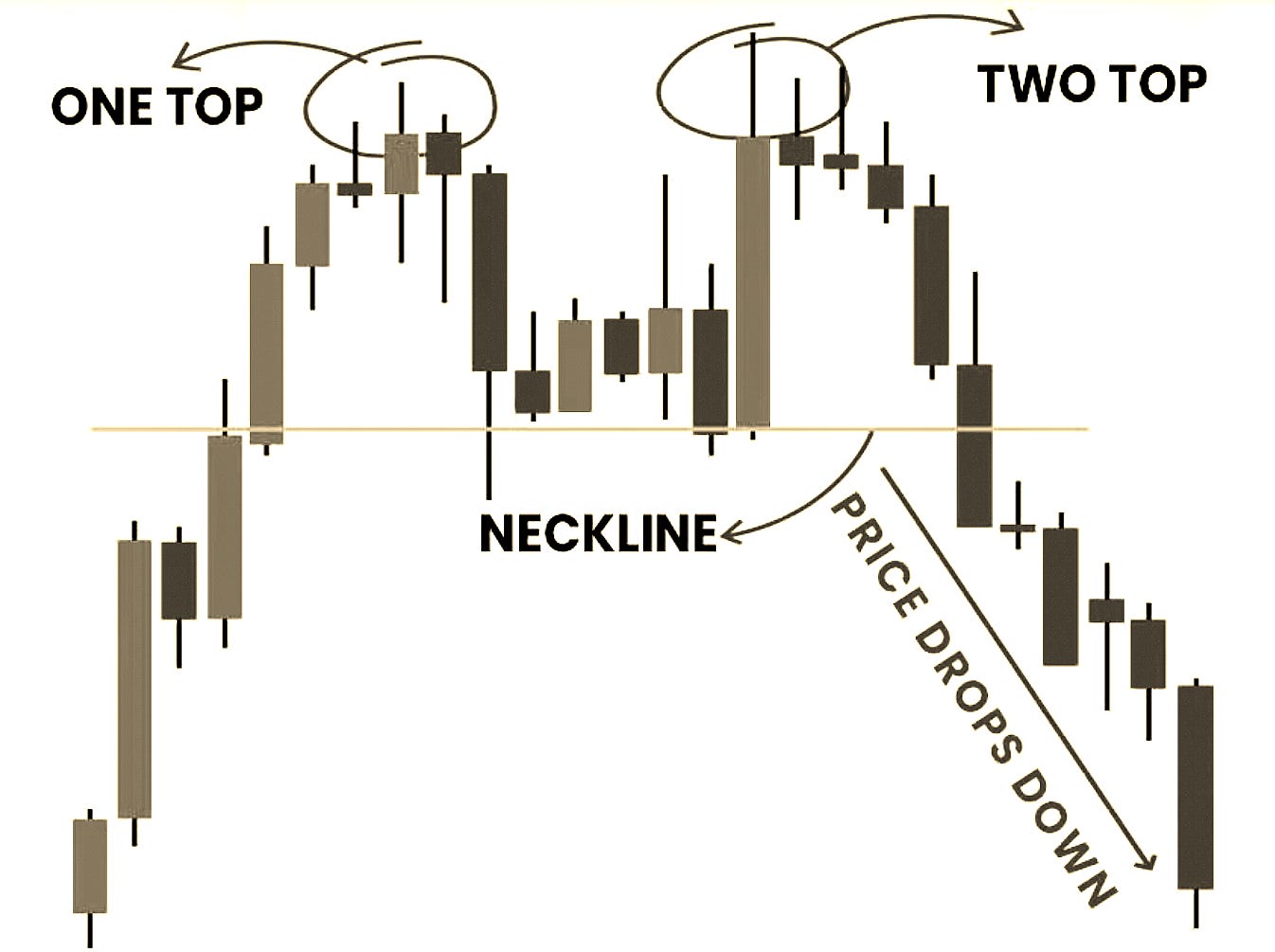

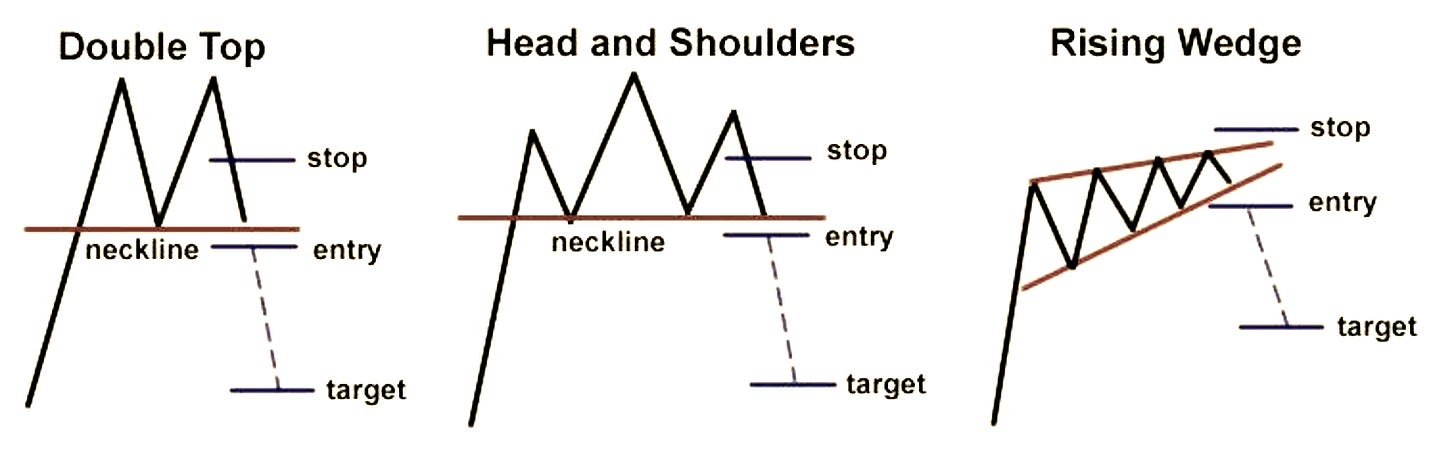

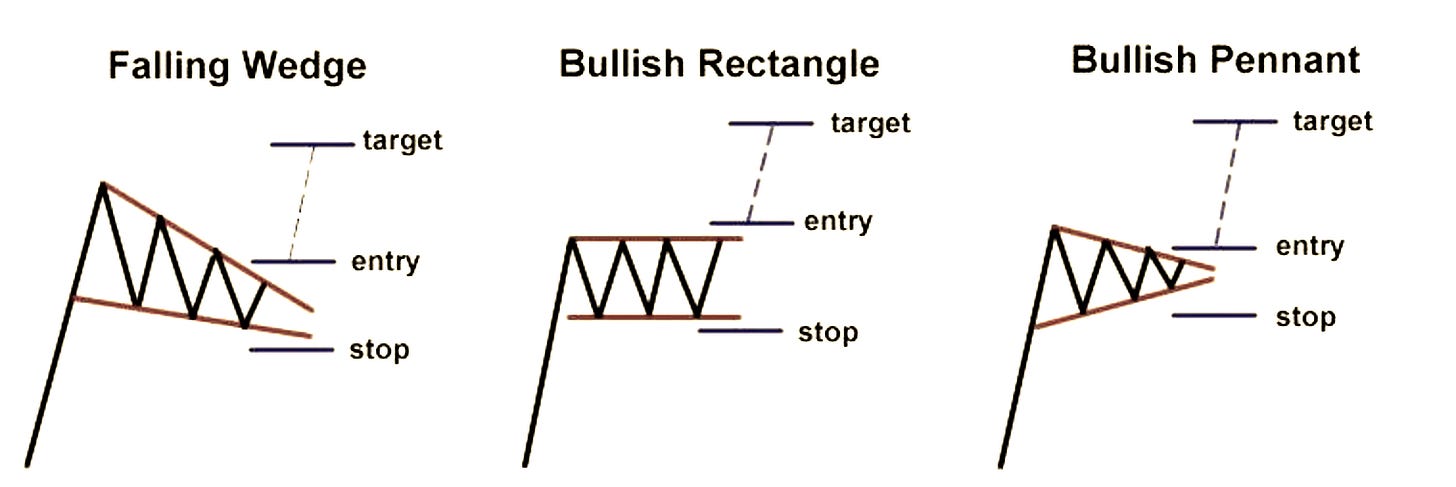

For example, when a double top forms, it often precedes a crash. Why? Because each time price approaches a resistance level, it draws in sidelined participants who believe the asset is overvalued and take short positions. When this rejection happens twice, it reinforces the belief that the price is too high—triggering a broader sell-off. Whether it’s a flag and pole, head and shoulders, or any other known pattern, all of them point to the same core idea: a divergence between the sample estimate of price and the true population price.

The future of the markets

All of these well-known price patterns were discovered by successful traders through years of experience. But what if there are other Patterns of Error—far more complex—still hidden in the noise? Patterns so intricate and nonlinear that they are imperceptible to the human eye.

In the future, the markets will be made efficient by AI agents capable of detecting and acting on these subtle inefficiencies faster and more precisely than any human ever could. AI is the next Warren Buffett and the future of markets will be won on Intelligence Arbitrages.

Naveen Benny is the founder of Prometéi Labs and a resident at Lossfunk. At Prometéi Labs, he is building a new age Quantitative Fund that is powered entirely by autonomous reinforcement learning agents.

Everything is priced in, even this blog is!!