Teaching morality to transformers

We train a custom transformers architecture on MIT Moral Machine data and run interpretability experiments on it

This is a summary of our paper that was accepted at Machine Ethics Workshop at AAAI, 2026: Building Interpretable Models for Moral Decision-Making

Preprint: https://arxiv.org/abs/2602.03351

Code: https://github.com/Lossfunk/modeling-moral-machine

Authors: Mayank Goel, Aritra Das, Paras Chopra

TL;DR:

We train a custom transformers model on MIT Moral Machine Data to make moral decisions on trolley problem-like problems

Through interpretability experiments, we found:

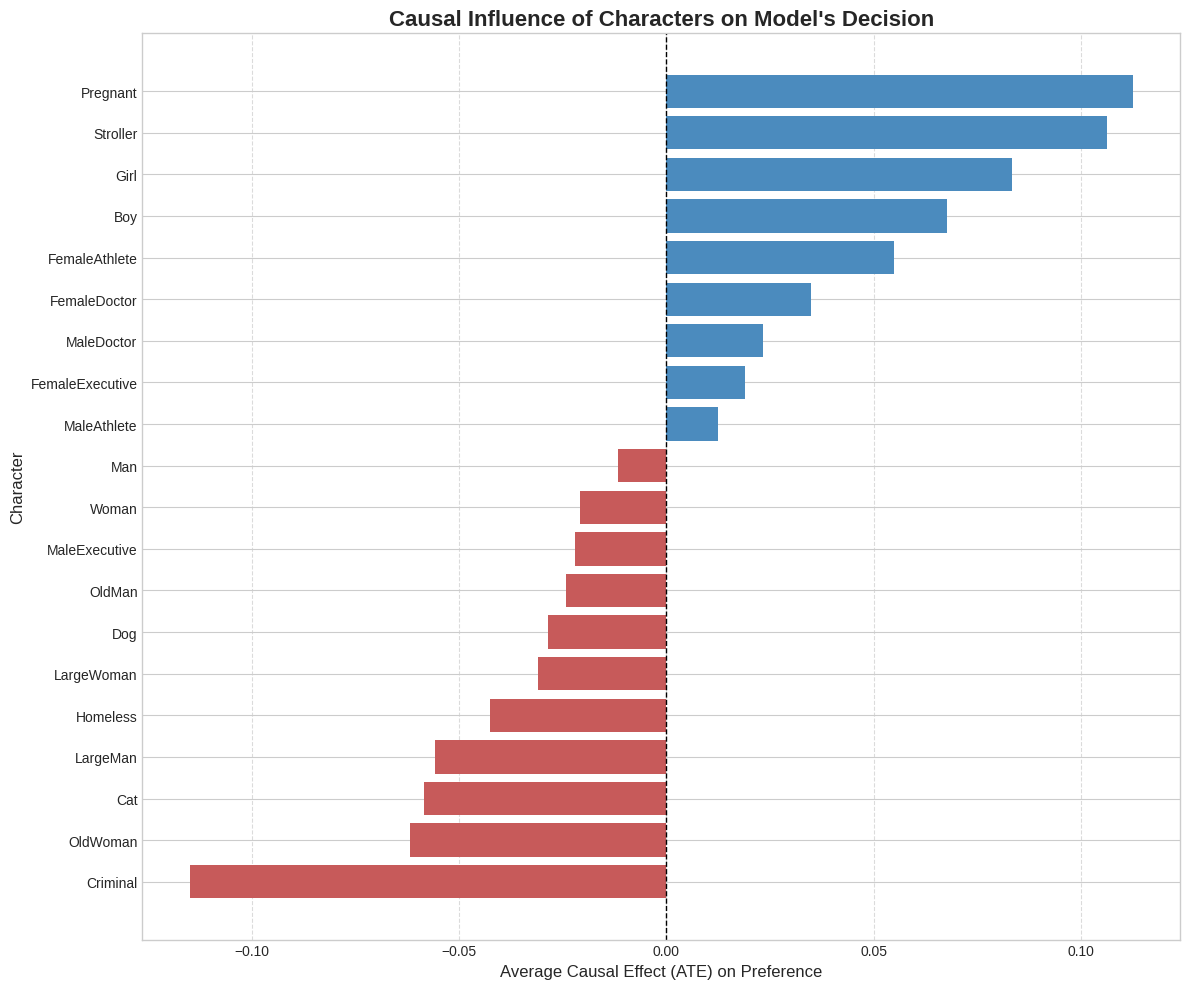

Causal influence: Characterstics like criminality, age, and species have the strongest effect on moral decisions

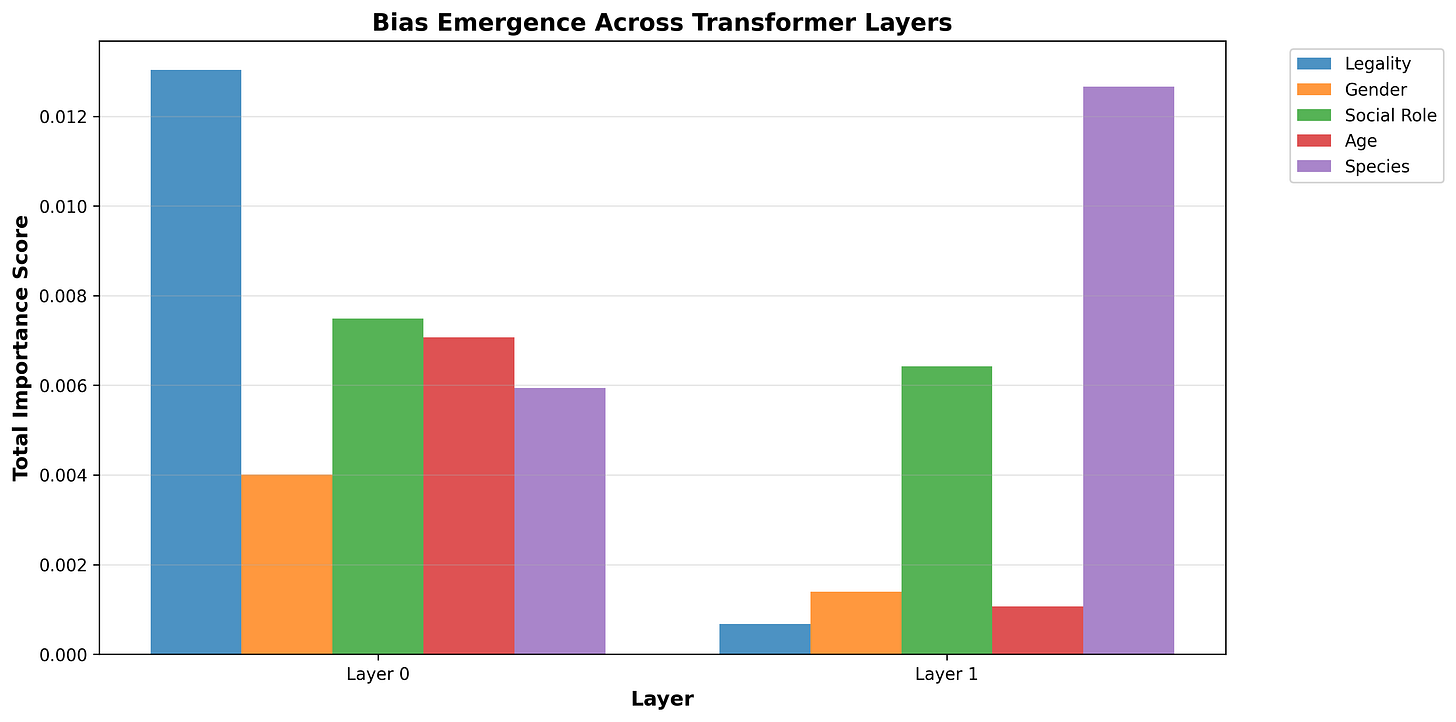

Layer specialization: Simple moral comparisons (legality, gender) emerge in Layer 1, while complex judgments (species, social status) develop in Layer 2

Head specialization: Different attention heads handle different moral axes

Sparse circuits: Only 17.6% of neurons are actually needed for moral decisions

This opens the door to safety applications like targeted debiasing - rather than needing to fine-tune the whole model, we can intervene at specific parts of the network to change the model’s moral reasoning

Morality is often considered subjective, and a largely qualitative decision. The trolley problem tries to get to the heart of utilitarianism - do we value saving the life of more people rather than less people, even at the cost of intervening? MIT Moral Machine data takes this a step further - rather than just comparing numbers of people, what is our preference when considering many different axes - such as dogs, cats, executives, doctors, homeless, children? They crowdsource these preferences from millions of comparisons - and released a dataset. We train a custom transformers model on this - and then try to understand what the model thinks about moral decisions - at the mechanistic level.

Architecture

There are 23 “features” that can be used to represent a particular choice: intervention, legality, type of character etc. Each feature can have a specific value; for characters it’s the number of that character present in this choice. We create a final 47-length “sentence”, 23 + 23 represent either of the choices and one [CLS] token which is ultimately used for decision making. Each token in this sentence is of 64 dimensions: made by concatenating the character embedding, cardinality embedding and the team embedding. This also means that we don’t use any position embedding in our model. The [CLS] token then goes to a MLP which finally outputs a 0-1 value, of how much it prefers Team A (0) or Team B (1). We train on 3.7M samples, and validate on 1.7M samples. While the training contains conflicting answers, we consider this a feature - as through many epochs, the model learns to hedge its bets and give values of around 0.5 for true dilemmas. We finally get an accuracy of 77% on the validation set, using a 2 layer, 2 heads model with 104k parameters.

Interpretability

We run several experiments on this model to learn how it thinks about morality.

Causal Intervention

To measure which characters causally influence the model’s decisions, we employ the DoWhy causal inference framework. We general 20k synthetic moral scenarios and construct a causal model for each character, and then finally calculate the Average Treatment Effect i.e how much does this character influence a moral decision, controlling for other factors such as group size. These results are also supported by our experiment using Local Relevance, following Chefer et al (2024).

Layer-wise Bias Localization

To identify where moral biases emerge in the network, we perform layer-wise attribution analysis by extracting attention weights from each transformer layer and correlating them with bias scores across five bias dimensions: legality (Criminal vs. law-abiding), gender (Man vs. Woman), social role (executives/doctors vs. homeless), age (children vs. elderly), and species (humans vs. animals). Through this, we were able to see that the first layer of the model learns simple moral comparisons, while species and social status are primarily learnt in the second layer. We were also able to see that the model localizes bias of a specific moral axes to specific heads - proving our hypothesis that the model engages in specialisation of moral decision making.

Circuit Probing

To check how dense (or sparse) our model is - we use circuit probing, which learns which neurons are responsible for computing specific intermediate variables by training sparse binary masks over a frozen model, then validates causality through targeted ablation while comparing against random subnetwork controls. We discovered a sparse circuit, which only used 17.6% of the neurons in the MLP to make decisions - removing which led to a 8.3% accuracy drop.

Wrapping up

The interpretability experiments show multiple interesting things about morality as learnt through the dataset- pointing out that the human notions of morality themselves can be learnt through training models on the data. The approach has clear limitations: training on aggregate human preferences inherits cultural biases. However, transparency enables new intervention strategies. Knowing criminal bias localizes to Layer 0 Head 1 allows targeted debiasing or clamping attention weights, rather than coarse dataset rebalancing or full model finetuning. We hope to extend this this line of work to traditional LLMs on moral questions. Future work along this direction will attempt to use this work as a base to explore larger LLMs on moral questions.

Mayank Goel, Aritra Das, Paras Chopra — Lossfunk Research