Your LLM is a confused oracle

We show that the forecasting accuracy of LLMs depends on what you ask and how you ask

This is the summary of our paper: Future Is Unevenly Distributed: Forecasting Ability Of LLMs Depends On What We’re Asking

You can find the paper link here: https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.18394

TL;DR:

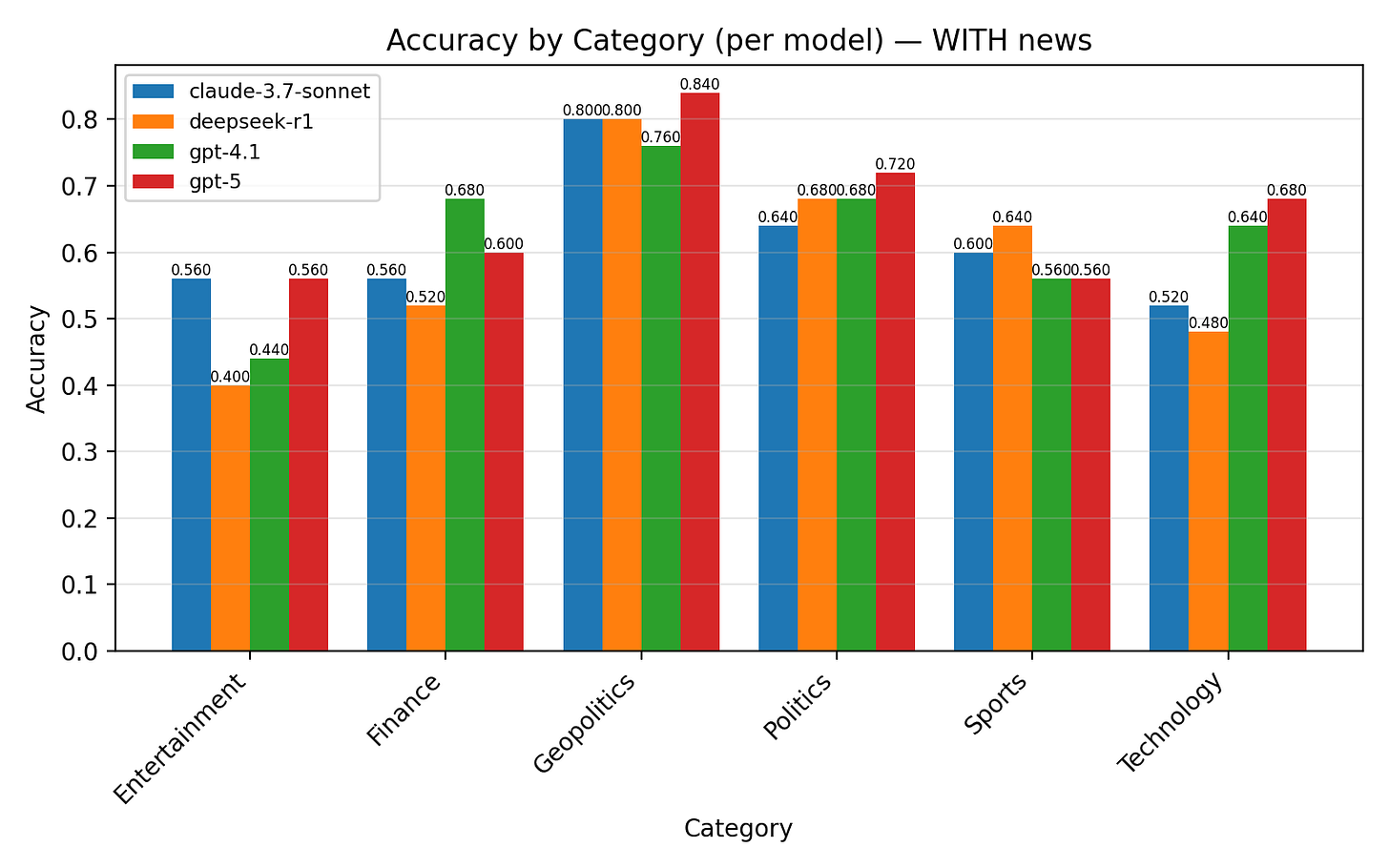

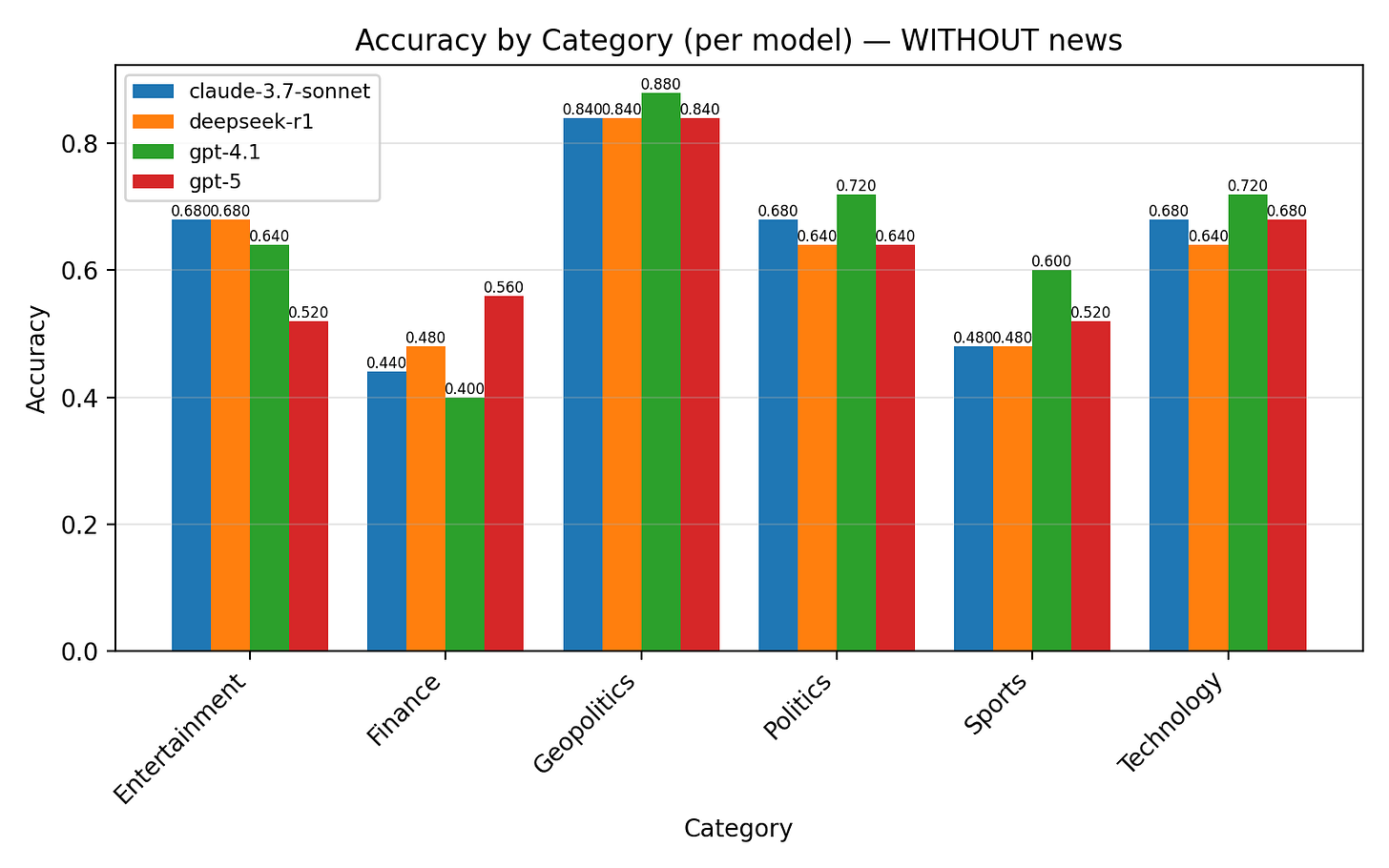

LLMs have different performance for different category of questions such as geopolitics, entertainment, finance etc.

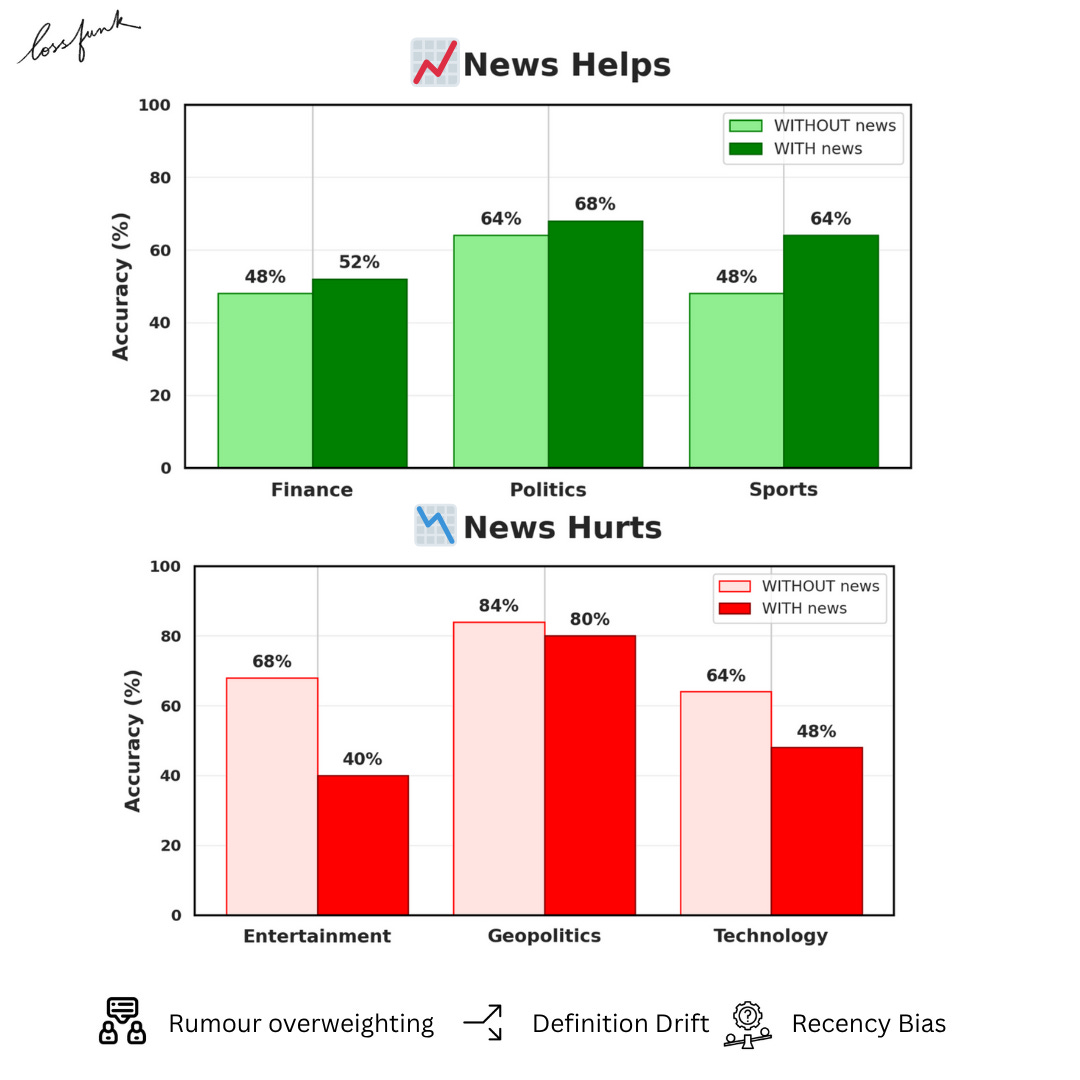

Addition of news context does help in some categories, but reduces accuracy in others

News induces failure modes such as definition drift, recency bias and rumor anchoring, which causes drop in accuracy v/s without news

As LLMs grow stronger and more “intelligent”, more avenues open up for testing their intelligence. We assume that like a normal person, as the person grows intelligent, they have a more generalised thinking process, but LLMs have a different kind of jagged intelligence.

They are superhuman in some areas, while being subpar in many others. We wanted to test this intelligence in real world forecasting scenarios, and thus devised a benchmark that could test this. We focused on forecasting ability as that requires genuine reasoning under uncertainty, and unlike math or reasoning, is still relatively under-explored with LLMs.

Benchmark Development

We began by collecting approximately 10,000 forecasting questions from various prediction markets such as Polymarket, Metaculus, and Manifold Markets, covering a period from January to July 2025. This period was chosen such that all questions selected were beyond the model’s cutoff date. Many of these questions were noisy - that is, their context was hyper-localized or didn’t properly require any forward-looking reasoning ability.

Some examples include:

“Daily coinflip”

“Will the % chance of ‘YES’ on this market close above 50%?”

“Will I get a Donation/Payment of 10,000 or more Mana before 2025?”

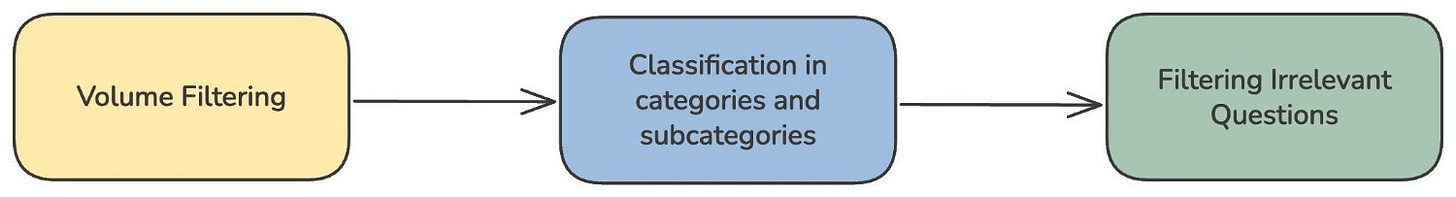

These questions do not provide any real signal of forecasting competence or reveal systematic failure modes. To extract a meaningful subset, we designed a three-stage filtering and classification pipeline.

First, we applied volume filtering to remove low-liquidity markets, which typically corresponds to hyper-personalized or creator-specific questions. Next, we employed an LLM-as-a-Judge to classify each question into six primary categories, each with five sub-categories:

• Politics: Domestic Policy, Elections & Campaigns, Political Parties & Ideologies, Government Structure, Public Policy & Social Issues

• Entertainment: Movies & Television, Music & Audio, Gaming, Celebrity & Pop Culture, Books & Literature

• Sports: Professional Sports, International Competitions, Individual Sports, Team Sports, Sports Culture & Recreation

• Technology: Computing & Software, Internet & Digital Services, Mobile & Consumer Electronics, Emerging Technologies, Tech Industry & Business

• Finance: Personal Finance, Banking & Financial Services, Markets & Trading, Economic Indicators, Corporate Finance

• Geopolitics: International Relations, Global Conflicts, Trade & Economics, Regional Affairs, Global Governance

Questions that did not align with any of the above were tagged as irrelevant, reducing the corpus to roughly 700 items after aggressive filtering. Despite this reduction, certain residual questions remained non-event-based and failed to meaningfully test predictive reasoning, such as:

“Will @Soaffine be active on Manifold again before April?”

To address these kinds of questions, we performed a second LLM-based filtering pass using a refined judging prompt to exclude localized or non-forecasting items. The final curated dataset contained 392 questions, evenly distributed across the categories and sub-categories listed above. For each retained question, we also preserved metadata such as creation time, resolution time, and final resolution probability.

Evaluation

We sampled a uniform subset of 150 questions from the final corpus, ensuring an equal number of questions per category to maintain a balanced evaluation set. This subset enables consistent cross-category comparison while preserving the representativeness of the larger filtered dataset.

We evaluated a mixture of reasoning-focused and non-reasoning large language models, including models from multiple families. All models were sampled at a temperature of 0.0, with a maximum token budget of 4500 tokens to ensure that they have enough room to express their reasoning. Deterministic sampling guarantees identical outputs across runs.

Each model received a standard forecasting prompt along with the question text and its creation date to provide temporal grounding. Apart from this contextual timestamp, the models had no access to external tools, retrieval systems, or web search capabilities.

For every prompt, each model outputs two fields:

<answer>YES/NO</answer><conf>0–1 confidence score</conf>We evaluated predictions using three key metrics: accuracy, the Brier score, and the Expected Calibration Error (ECE).

Accuracy measures whether the model’s predicted resolution matches the actual market outcome. A correct prediction contributes 1, and an incorrect prediction contributes 0; the mean across all samples yields the final accuracy score.

Brier Score quantifies probabilistic calibration by penalizing confidence errors. It is defined as:

where f_i is the model’s predicted probability for a “YES” outcome, and o_i ∈ {0,1} represents the ground-truth resolution. Lower values indicate better probabilistic accuracy.

Expected Calibration Error (ECE) measures the discrepancy between predicted confidence and empirical accuracy across probability bins. Predictions are divided into bins based on confidence, and ECE is computed as:

where B_m contains predictions whose confidence scores fall into bin m, acc(B_m) is the average accuracy within that bin, and conf(B_m) is the mean predicted confidence. Lower values indicate better calibration.

Evaluation with News Context

For the second evaluation condition, we augmented each forecasting question with external context retrieved from contemporary news sources. This ensured that models received the same type of information a human forecaster would have had when the question was originally posed. We collected recent news snippets for each question by querying a news retrieval system using the question’s creation date as the upper bound for publication time. Occasionally, we observed leakage in the form of articles published after the creation date; such snippets were removed to preserve temporal purity.

Each model was then re-evaluated on the context-augmented version of the dataset using the same scoring metrics as before accuracy, Brier score, and ECE. This second evaluation condition enabled a direct comparison between forecasting with and without external context, and allowed us to measure how models incorporate and utilize additional information.

In general, adding news context sharpened forecasts and improve calibration for many models, offering a finer measure of reliability beyond raw accuracy. Some models showed strong calibration gains in domains such as Geopolitics and Politics, while others displayed higher ECE in noisier categories like Entertainment and Technology.

Flaws induced due to news context

While the additional news context often sharpened the temporal interpretation of a question and helped isolate relevant signals, it also introduced several failure modes. We highlight some of the most common ones.

Recency Bias

Models tend to overweight recent news compared to historical context encoded during pretraining. This often causes the model to shift a correct resolution into an incorrect one simply because the latest headlines dominate its reasoning.

Question: “S&P 500 above 6050 on June 13?”

Raw model (a): NO, 0.34 confidence. The model cites resistance at 6000 and mean reversion, interpreting limited trading days as making a breakout unlikely. (Correct)

News model (b): YES, 0.54 confidence. It reads snippets from the days before June 13 describing the S&P “flirting with 6000,” “record highs,” and “strategist upgrades targeting 6100.” (Wrong)

The model allowed the most recent headlines to override its prior reasoning, turning a correct mean-reversion call into an overly confident breakout prediction.

Rumour Overweighting

Models frequently anchor to unverified or speculative information present in retrieved news snippets. This can push them toward resolutions that contradict actual events.

Question: “Tariffs on China above 150% by end of June?”

Raw model (a): NO, high confidence (0.85). It cites policy friction and procedural requirements. (Correct)

News model (b): YES, 0.65 confidence. After reading reports from late April and May discussing the possibility of tariffs “rising toward 150%,” the model shifts to an overconfident YES. (Wrong)

In reality, headlines only suggested the possibility, not an enacted policy. The correct outcome required actual implementation by the deadline, which did not occur. The model overweighted rumour-like indicators and underweighted the lag between proposal and policy execution, flipping a cautious, process-aware answer into a headline-driven one.

Definition Drift

Models sometimes misinterpret acronyms or context when additional news shifts their semantic grounding, leading to incorrect predictions.

Question: “Will MATS applications open in March?”

True resolution: YES

Raw model (a): YES, 0.58 confidence. It interprets MATS as the recurring academic program that historically opens applications each March, referencing prior cycles. (Correct)

News model (b): NO, 0.35 confidence. It reinterprets MATS as the Mid-America Trucking Show after reading recent news coverage, where registrations open months before March. (Wrong)

With added news, the model anchored to the recently more prominent trucking show from the retrieved articles instead of the academic program. This shifted its reference domain and thus the expected timeline, leading to a misplaced “NO.” The model underweighted contextual clues from the original question (academic cycle, application deadlines) and overweighted irrelevant industry news, producing an incorrect forecast.

Why is this study important?

As artificial intelligence systems are increasingly more integrated in decision making with governments (such as in Albania’s case), it becomes more important that the capabilities of these language models are studied and known to know of their shortcomings and strengths.

This is an important question that we must ask about the reliability of LLMs in forecasting abilities and decision making, and so as to make better informed and aligned assistants in the future.

Conclusion

We find that models are more intelligent in some areas than others, especially in real world forecasting benchmarks, and are prone to issues with added news context.

Read the Full Paper

You can find the paper link here: Future Is Unevenly Distributed: Forecasting Ability of LLMs Depends on What We’re Asking

Chinmay Karkar & Paras Chopra — Lossfunk Research

📧 chinmay.karkar@lossfunk.com | paras@lossfunk.com

The recency bias example with the S&P 500 really resonates here - it perfectly ilustrates why blindly adding context can actully hurt reasoning. That overconfident YES when the model should've stuck with mean reversion logic is such a powerful failure mode to highlight. Makes me wonder if there's a way to weight historical context more competitively against fresh headlines?

what was the prompt used for these models tho? that probably played the biggest factor for all of these predictions , if the models were asked to imitate an expert and be skeptical like a human would be after watching news for a while , the results could be very different