How to choose research problems

TLDR: balance between what your heart says and what the community will value

This article is continuation of our series where we explore the meta-science problem of how to go about science.

Previously, we’ve written about:

Picking a research problem is often said to be the key component of what constitutes your research taste. That’s because often the impact of research is downstream of what kind of problems you pick up.

So, the problem you pick up in your research will have a disproportionate impact on your research career, making the choice extremely important.

In this article, we compile tips and advice from other researchers on how to choose a research problem.

How To Choose a Good Scientific Problem

https://www.cell.com/fulltext/S1097-2765%2809%2900641-8

Why start a lab?

A lab is a nurturing environment that aims to maximize the potential of students as scientists and human beings

Impact

Problems can be ranked in terms of the distance from the known shores, by the amount in which they increase verifiable knowledge.

How to choose

most often we would like problems in the top-right quadrant, both feasible and with high interest, likely to extend our knowledge significantly.

Pareto optimality - if problem A is better on both (impact - knowledge generated, and feasibility) than problem B, erase problem B.

Beginning students need to weigh feasibility more

Positive feedback can do wonders

PIs need a grand challenge - hard but can create large gain in knowledge

Take your time to commit - read, discuss, plan

Choice of problem has more impact than anything else on your research output

Interest can be broken down into two components

Impact - downstream impact, what others want

Neglectedness - what wouldn’t happen if you don’t do it, what’s in your heart?

What Problems to Solve - By Richard Feynman

http://genius.cat-v.org/richard-feynman/writtings/letters/problems

“A problem is grand in science if it lies before us unsolved and we see some way for us to make some headway into it”

I would advise you to take even simpler, or as you say, humbler, problems until you find some you can really solve easily, no matter how trivial. You will get the pleasure of success, and of helping your fellow man

An Opinionated Guide to ML Research

http://joschu.net/blog/opinionated-guide-ml-research.html

Choosing problems

Ability to work on the right problems is even more important than your raw technical skill - this is what research taste is

Idea driven v/s goal driven research

Idea driven - you read a paper and you get an idea on how to do X even better

Make X better

Goal driven - you have a vision of what you want to explore (e.g. RL for 3d locomotion)

Make X work for the first time

Goal driven is better as idea driven has too many people chasing the same problems as they read the same literature, while the goals you set are uniquely yours, and hence differentiated.

Goal driven is also motivating as you chose it

Pitfall of goal driven research - do it in such a specific way that it doesn’t advance the field

You should try to constrain your approaches so that they’re general and can be applied to other problems

Aim high but climb incrementally

When choosing problems, ask yourself: if you solve it, what’s the potential upside? 10% improvement or 10x jump

Incremental advances should be simple/easy, otherwise nobody will use them.

How (not) to choose a research project

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/kDsywodAKgQAAAxE8/how-not-to-choose-a-research-project

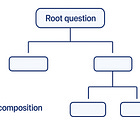

Start with your main top problem, and then decompose it to sub-problems (these are what makes the top problem hard to solve or we have a major unknown)

Select a subset of problems that seem important and can be grounded in reality (have fast feedback loops)

Tips:

Don’t propose solutions until the problem has been discussed as thoroughly as possible without suggesting any

People get attached to their solutions

Do experiments that will give a “firehose” of information, even if you fail. Maximize what you learn from each experiment

Work on what you find interesting - hard to be motivated by anything else

Work on concrete subproblems where you can have fast feedback loops

Know what success looks like for your project

What advice do I give to my students?

https://thoughtforms.life/what-advice-do-i-give-to-my-students/

Michael Levin’s advice on life, science and ideas

“What to do”

Think about happiness in 10-20 years from now - hedonic (here and now) and eudaimonic (long term meaning & satisfaction); it’s hard to have both - one has to be strategic, lucky, energetic and self-aware to be in a spot where you can have both.

Are you the person who values daily journeys, or the specific destinations?

Do you want to optimize total output and impact that you facilitate, or the amount of it that you personally do?

“Pick the hill you’re willing to die on, and focus your story there”

Focus on your main, specific idea or the big thing you want to talk about, and don’t include ancillary claims that will irritate readers and open multiple fronts.

On criticism of your ideas

Visualize yourself as a glass - nobody can see or criticize you. All they can see is your ideas and results, not you.

On people “stealing” your ideas

In science, that’s a win!

But, it’s so hard to convince others that by the time they do it, you should be somewhere else intellectually

On “impact”

It’s so hard to measure (with so much noise) that thinking about it can dissuade easily

Find a middle ground between your curiosity/passion/heart’s desire and your “theory of change” (i.e. how you want the world to be different because of your efforts)

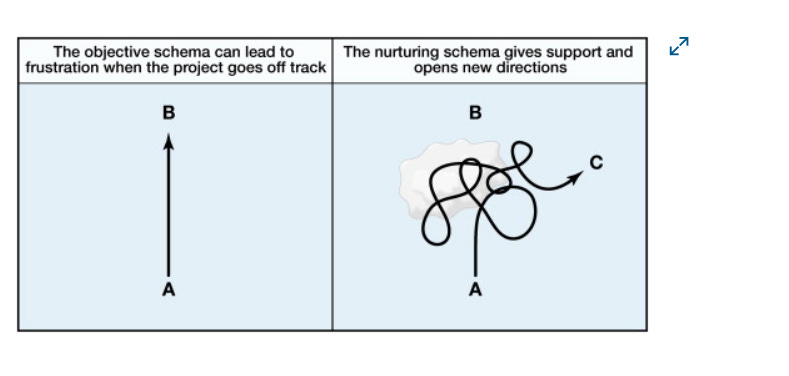

On "balancing" your efforts

Keep your one side tuned to making your work heard in a community from a very practical sense, taking into account others’ opinions. This side exists to please a community.

Keep your other side pristine - don’t let others’ opinions enter into how you think. This side doesn’t please anyone.

Read broadly

Especially outside of your main field, and ask basic, fundamental questions in it

On “ideas”

Teach your mind that ideas are important by writing them (not just remembering them) and then working with them

Final: “visualize your future lab”

Imagine your lab already existed, what does it look like? What discoveries is it known for?

This helps jog your mind in random, fruitful directions.

The author, Paras Chopra, is founder and researcher at Lossfunk.

I think the same can be applied in choosing the problem for working on one's startup/business... Please share your thoughts on what not (if any) & what else from "how to choose research problem" we should look for when choosing startup problems?